Bukowski, Misogyny, and the Question of Good Art by Bad People

By Audrey Treon

I finished reading Hot Water Music (1983) in February. I bought it for two reasons. 1) It looked right up my alley. I love a short story, especially one that gets deep under your skin, expressive of the grimy, violent nature of humanity — I want to lose myself in those pages. 2) I’ve always wanted to read Charles Bukowski’s work. Why? Because he’s Bukowski. And because of that, I should read his work. That’s really the only justification I had.

I knew he was a terrible misogynist going into my reading. And for that reason, I thought I could look past the bigotry because I would be in the presence of great literature.

As it turns out, I couldn’t look past the bigotry. I know, I know, that’s part of his appeal — his unapologetic disgustingness achieved with minimal diction, his ability to dive into the depths of the depraved mind. My love for each chapter quickly dwindled when I got to a line that read something along the lines of “She began to masturbate.” “She farted as we fucked.” “Her tits were disgusting, just like her face.” (These are just the first ones that come to mind.) These punchy declarations were formative to the story — no matter the bigotry behind them.

Hot Water Music’s most frequent character is Henry Chinaski, Bukowski’s literary alter ego. He is a pervert, a drunk, a writer, a raging misogynist, and a damn entertaining character. These traits come together against the backdrop of 20th-century Los Angeles, with polluted sunsets, loveless sex, hookers, scotch, and a perpetual cloud of cigarette smoke — the perfect storm for a man like Chinaski.

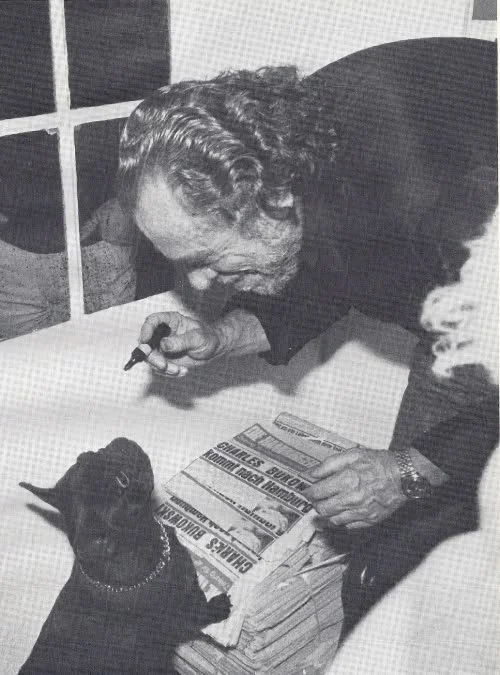

Image Sourced from Pinterest

I realize that in some — hell, even most — cases, the sexual and gendered depravity mean something to the story — it isn’t there for no reason. I think that’s my issue: Said depravity was there for multiple reasons. It added to the story, developed the character, and was representative of Bukowski’s misogynistic ideology. I can’t separate one from the other — his characters come from him, his brain. But do I really want to read 221 pages of a sexist man spewing words like “bitch” and “cunt” at me? I don’t know.

Like I said, I love a gross book as much as a gross character. I am not by any means bored by morally clear characters, but damn it do I love a fucked-up character — one that exists within the grey areas of morality, even beyond it, surrounded by a cloud of impenetrable black. Chinaski is just that.

Does an author’s use of politically incorrect words or themes render their writing “bad?” Should it discourage us from reading it altogether? People often reference alt-right pipelines and just how easy it is to fall into them. But does a Bukowski book hold the same danger as something more explicit, like an incel-infested subreddit? I don’t think so. Despite my mixed feelings towards Hot Water Music, I can recognize the nuances and sheer talent of a man like Bukowski. Art is a tricky thing — people have wildly different definitions of the word itself. Bad art by bad people is a whole lot easier to ignore than good art by bad people.

I do not expect nor desire the authors I read to be perfect people; perfect people can’t write. But I do not want the authors I read to be bigots. With that being said, a lot of great literature would be lost without the bigots, a lot of great art. And yeah, I did not love writing that sentence. So, how do we go about reading a Charles Bukowski book, purchasing a John Galliano garment, watching a Hollywood blockbuster starring a known abuser, and existing in a world with a lot of fucked-up and greatly talented people?

Image Sourced from Pinterest

I don’t know, and I find a strange peace in that. I am not perfect (granted, I’m not a bigot, unlike some people…) but, nonetheless, there is a sense of freedom in accepting that some people are, at a very base level, not people I want to be around, not nice nor “good” people in my book. Though simple, this can be a hard pill to swallow: there is a lot of great art by a lot of bad people. We must expose ourselves and interact with said art, not to seek to understand the artist’s justification, not to find a way to forgive them, but to experience art for what it is — imperfect. How irresponsible it would be to read a book like Hot Water Music and not dare to interrogate the social implications of such writing.

I, like we all do, find myself within the gray areas of perfection — I walk in a cloud of silver. I don’t expect or want the artists I interact with to be perfect, and I should hold that standard for myself. We are all making imperfect, flawed decisions, and sometimes, those are for the betterment of ourselves.