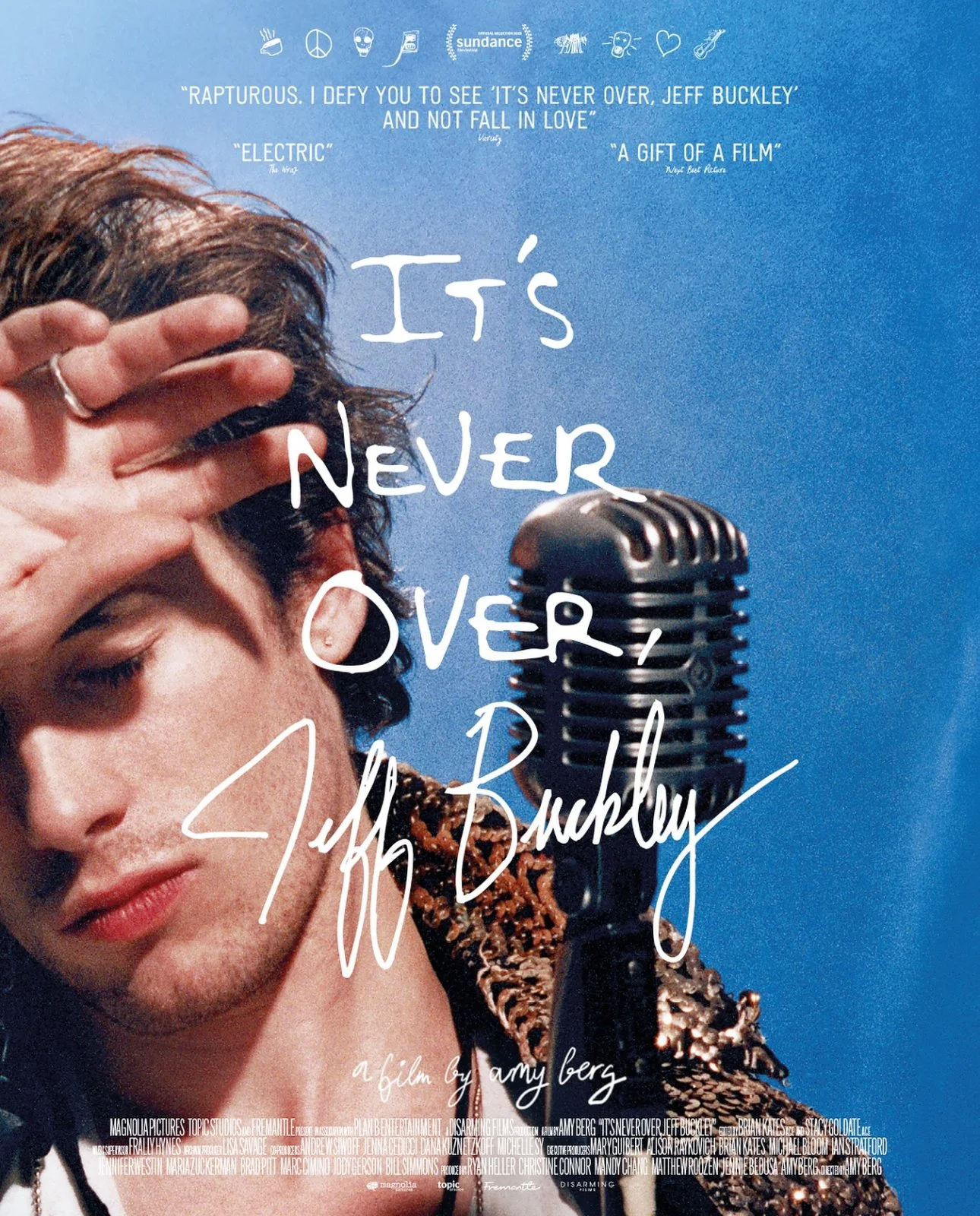

Lover, You Should’ve Come to the Theater: 'It’s Never Over, Jeff Buckley' Reviewed

By Natalie McCarty

“Because without no ordinary life, there’s no art.”

The new documentary directed by Amy Berg, It’s Never Over, Jeff Buckley, opens and closes on that paradox: the collision of the ordinary and the transcendent, and it is precisely in that tension that Jeff Buckley lived, created, and died. For an artist who left behind just one studio album, his impact has remained seismic. His 1994 debut Grace still sits in the pantheon of the best records of all time, haunting a generation that never saw him live (myself included) and still commanding reverence among musicians who recognize the rare thing he was: a man who could sing like an angel while writing like he was running out of time.

This film, directed with a tender but unsparing hand, tries to answer a question that has hovered like incense smoke around Buckley since his death in 1997 at age 30: who was Jeff, really? Was he the tortured genius? The golden-voiced romantic? The reckless self-saboteur? Or was he, as his closest friends, lovers, and family suggest, just a guy trying to stitch together a life in the middle of contradictions too big for anyone to reconcile? A son abandoned by a father whose very voice he had inherited? A young man whose love affairs often were collisions between tenderness and destruction? A dreamer who wanted to live more life than this world could ever offer?

The film doesn’t mythologize him. If anything, it dismantles the myth. Through archival footage, grainy home videos, and interviews with his mother Mary Guibert, ex-girlfriends, bandmates, and friends, It’s Never Over, Jeff Buckley reveals not a flawless idol but a man who lived vividly, brightly, and daringly. What emerges isn’t only Jeff Buckley the legend, but Jeff Buckley the person.

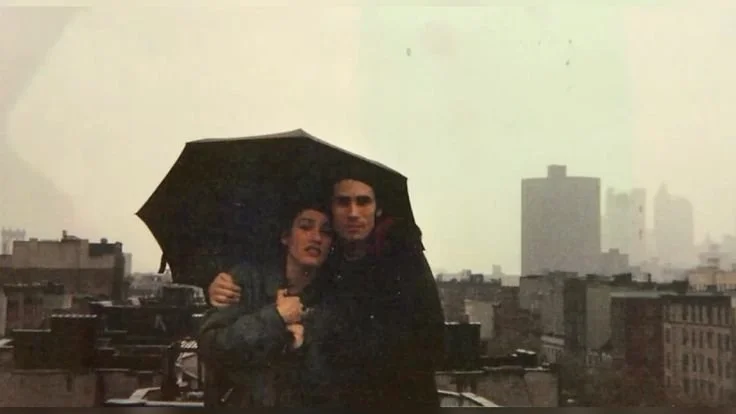

If the documentary has a beating heart, it is the presence of Rebecca Moore and Joan Wasser. Their reflections are deeply personal and unvarnished, giving viewers an intimate lens on the man behind the myth. Moore, Buckley’s first love in New York, speaks not only of desire but of inspiration. She recalls the dizzying, almost hallucinatory intensity of their connection and the spark of creation that always seemed to flicker between them.

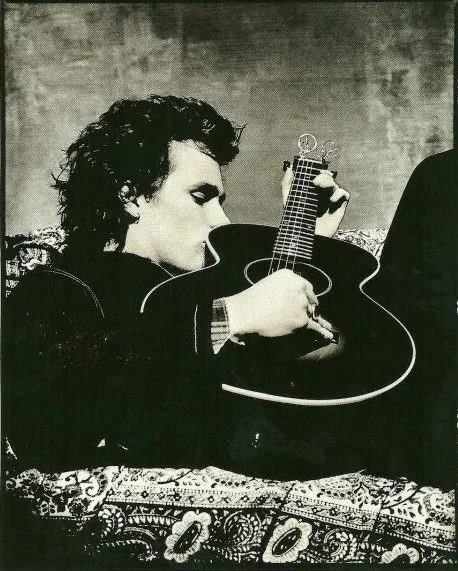

Wasser, herself a musician and longtime partner, adds another layer. Her recollections are gentle but piercing, highlighting a man whose generosity of spirit was matched by his restlessness. Watching her describe moments of their relationship built on creative collaboration, shared laughter, and collective struggles, it becomes clear that Buckley’s life with these women was as much about learning to navigate the extremes of love as it was about performing or writing music.

The film explicitly evokes a Dylan-Rotolo-Baez dynamic: that intricate triangle of muse, lover, and artistic gravity. Moore as Rotolo, Wasser as Baez, and Buckley as Dylan (his hero, might I add) orbiting between them. A collision of friendship, romance, admiration, and yearning that is almost palpable on screen. It is a quiet, understated drama of the heart, punctuated by glances, song lyrics, and images of shared kisses, all set to the music that he was creating in those very moments. You feel the push and pull of inspiration and longing; the camera lingers on hands, on eyes, on small gestures, and you understand that these relationships were as central to his art as his guitar.

In one of the film’s most affecting turns, Rebecca Moore reflects on the intensity of loving someone whose art was inseparable from his being. Her memories don’t glamorize him; they carry the ache of a relationship lived in the shadow of his music, of nights when tenderness collided with his persistent drive to create. Later, Joan Wasser speaks with both warmth and sorrow about their time together, recalling not just the joy and brilliance Jeff radiated, but also the fragility and volatility that came with it. These testimonies aren’t dramatized; rather, they are lived in. In their familiarity, they strip away myth and reveal the pulse of his creative soul. And it brings you all the closer to him.

Through Moore and Wasser, we see the duality that defined Buckley: tender and reckless, present yet ephemeral, capable of profound love yet unable to fully anchor himself in it. The documentary brings a new layer to his discography and contextualizes each note, each falsetto, as a reflection of the love, longing, and heartbreak he carried with him. Love, for Buckley, was both muse and mirror, and the film allows the audience to witness it in real time, making the emotional impact of his art all the more immediate.

Culturally, Buckley has always been a figure made of fragments. Much to his dismay, he was first introduced as the son of Tim Buckley, the folk-rock singer who abandoned him and died at 28 of a drug overdose. Jeff inherited not only his father’s eerie vocal timbre but also the absence of a role model, a void that would shadow his life and work. It’s Never Over, Jeff Buckley handles this legacy with care and lingers on the cruel irony: to spend your life sounding like the man who left you, to carry in your very voice the echo of someone else’s mistakes. It was both his burden and, in some ways, his inherited destiny.

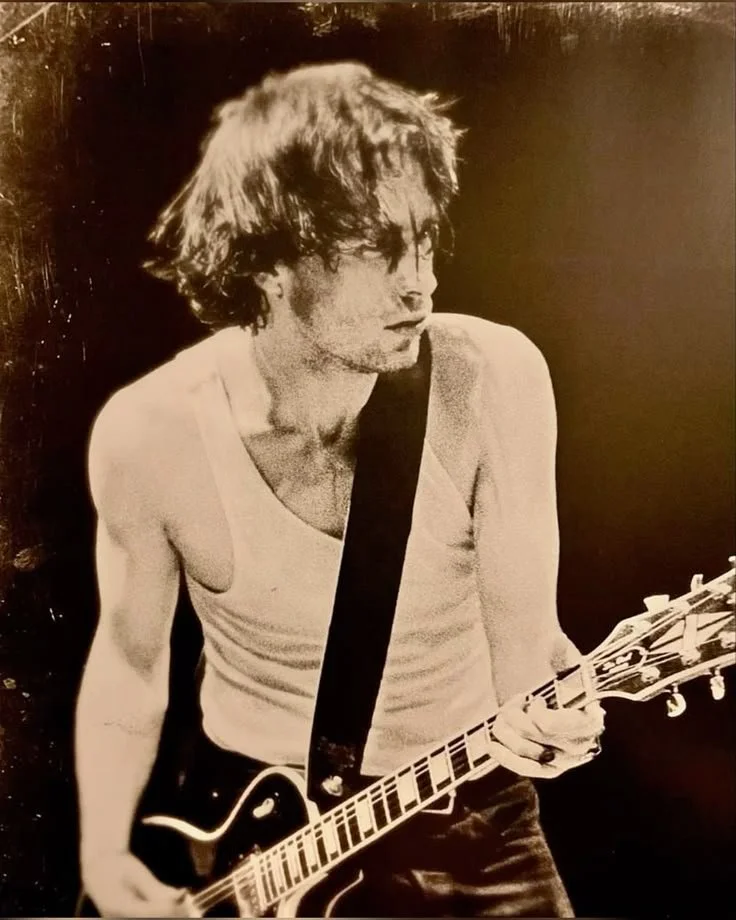

The director, Ann Berg, avoids the trap of linear biography. Instead of cradle-to-grave, we get a mosaic. Old performance clips bleed into lovers’ recollections. Personal memories layer over concert footage. The style evokes Montage of Heck’s attempt to capture Cobain’s fractured psyche, or Moonage Daydream’s kaleidoscopic Bowie (who once called Grace the greatest album he’d ever heard). But here, it feels truer to Jeff than you could even imagine.

The editing deserves special credit. One moment, you’re in the crowd of a small club watching him break open “Mojo Pin.” The next, Moore or Wasser recounts a private joke, a late-night argument, or an impromptu jam session, and the collision of intimacy and distance mirrors the experience of listening to Buckley. Gutteral, tender, whimsical, strained.

For me, Buckley has always been more than a figure in music history. Beyond my affinity for him, he’s always felt like an uncanny, almost spectral presence in my own life. Born in Anaheim, just fifteen minutes from where I grew up, he later lived in New York in an apartment only two blocks north of mine. To walk those same streets was to feel his ghost brushing past. To feel reminded that art belongs in the places we inhabit, in the ordinary sidewalks of our lives. Sometimes, those are the most remarkable.

They’re also certainly the most memorable. At eighteen, sick with heartbreak and hungry for something larger than myself, I ran from E. 10th to 97th with Grace on repeat in my headphones, his voice my companion. The tune sung to moments spent sitting in the fountain of Washington Square Park. Or when exhaustion and grief had hollowed me out, it was “Forget Her” that looped for three days straight as an incantation of my sadness. Also streamed in Vermont’s forests and by its creeks. Or when I let go of a life I couldn’t keep — driving in Montauk, heading home to Los Angeles with my mother — “Lover, You Should’ve Come Over” was there, soundtracking the moment like it had been written for me alone. I just love that album; I love Jeff Buckley.

What It’s Never Over, Jeff Buckley communicates so powerfully is that his relationships, whether romantic, platonic, or familial, were never incidental. They were entwined with his music, his emotional life, his art, and his legacy.

There’s always a danger in how we handle artists who die young. The temptation is to romanticize them into martyrs, to make their tragedy part of the allure. Amy did this with Amy Winehouse, Montage of Heck with Cobain. Buckley is often painted in the media with the same brush: doomed musical talent, too fragile for the world.

But It’s Never Over, Jeff Buckley resists that cliché. It shows his humor, his feminism, his appetite for life. He wasn’t just some tortured poet; he was goofy, restless, deeply alive. That’s what makes his death all the more tragic, as he wasn’t destined to die young; he just did. And randomness is harder to digest sometimes.

If the film falters, it’s in leaning too heavily on secondhand testimony at times. The moments where we hear Jeff— really hear him— are the most electrifying: his interviews, his diary entries, his voicemails, his live onstage performances. Those fragments remind us that no one could narrate Jeff’s life better than Jeff himself. But the director’s decision to center his mother, Mary, is wise. Her tenderness grounds the film, giving us a counterweight to the absent father. Watching her remember her son is the film’s most gut-wrenching gift.

Ultimately, It’s Never Over, Jeff Buckley isn’t just a documentary about a musician. It’s about what music does to us, especially his. How it burrows into memory, how it resurrects the ages of our lives we thought we’d left behind. Watching it, I was eighteen again. I was young and desperate, feeling every heartbreak as though it was the end of the world and every kiss as its salvation.

Jeff once said, “You can achieve a real state of grace through someone else’s love in you.” The film makes you believe it. And maybe that’s why, decades later, Buckley still feels so relevant. He isn’t a relic of the 1990s, not just another tragic rock story. He is proof that an ordinary life, when lived with abandon, can echo forever.

It’s never over.