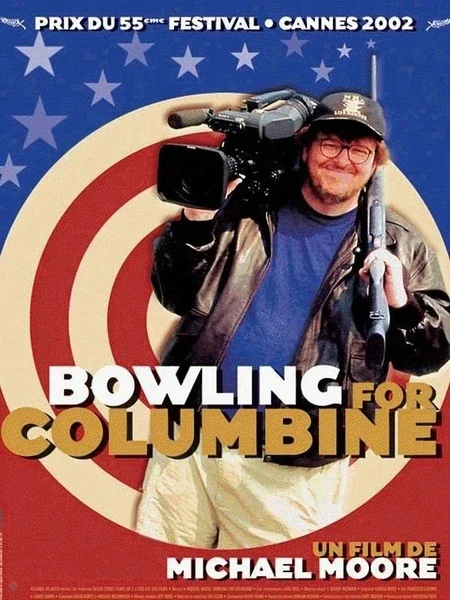

Should I Be Afraid? The Climate of Fear in 'Bowling for Columbine'

By Julia Krys

When I tell people what Bowling for Columbine is about, the response is often: “Too sad. I can’t watch that.” I understand the instinct. I grew up in Colorado, where gun violence was not an abstract concept. From the 2012 Aurora theater shooting that made me afraid to go to the movies through my teen years, to the 2021 Boulder King Soopers tragedy, to the most recent shooting in Evergreen—there’s more than enough sadness to make me want to turn away from the subject. For years, I did. But watching Michael Moore’s film made me grateful he dared to do the opposite.

Moore’s documentary doesn’t dwell on Columbine as a heart-wrenching retrospective. Instead, it uses the 1999 massacre as a doorway into bigger questions: Why does this keep happening? How has America cultivated the conditions for such violence to thrive? Those are the questions that still haunt us, more than 20 years later.

Image Credit of Festival de Cannes

The film begins with a detail as eerie as it is inexplicable: the Columbine shooters went bowling the morning of the attack. Moore doesn’t try to solve that mystery. Instead, he frames it as a metaphor for the unknowable aspects of human violence. Just as we’ll never understand why they bowled, we can’t always pinpoint why someone pulls a trigger. From there, Moore takes us on a journey through the social, political, and cultural forces that make such tragedies possible.

One of his first stops is his hometown of Genesee County, Michigan—a place steeped in gun culture. When asked why they love their firearms, locals repeat familiar refrains: “It’s my right” and “I need to keep myself safe.” But as a viewer, watching someone cradle a gun reads less like security and more like a threat to everyone else’s safety. Moore, a lifelong NRA member himself, uses this insider position to disarm his subjects. They assume he shares their worldview, and when he bluntly challenges it, the disconnect is striking (and even humorous), like they’ve never considered that guns might endanger innocent people more than they protect them.

From there, Moore broadens his scope to an international comparison that remains one of the film’s most dumbfounding segments. Canada, like the U.S., has a strong gun culture rooted in hunting traditions. Yet Canadians don’t endure mass shootings at anything close to America’s rate. Why? Moore suggests it’s not the sheer number of guns but the climate surrounding them. In Windsor, Ontario, he finds residents leaving their front doors unlocked. When he asks if they’re worried about crime, one responds simply: “Should I be afraid?”

That question hangs in the air. In America, fear is the default setting. We live in a country where studies show most people believe crime is rising even when data proves it’s falling (Pew Research Institute). Moore points to the media’s relentless focus on sensational, violent stories; a trend that’s only grown more toxic since the film’s 2002 release. Social media has amplified the same fear-driven cycle, feeding us a steady diet of chaos until it feels like the world is constantly on the brink of collapse.

This culture of fear seeps into everyday life. After Sandy Hook, “active shooter drills” became routine in American schools. I remember explaining them to international classmates in college. Many were stunned such exercises even existed. And yet, research shows these drills offer little real protection while instilling deep anxiety in students (National Academies). They are rituals of fear more than safeguards against danger.

Image Credit of AP/Scottbot Designs

By the time I finished Bowling for Columbine, I couldn’t believe I’d put it off for so long. It’s less like a documentary and more of a mirror Americans are still reluctant to look into. Two decades later, Moore’s diagnosis hasn’t aged—it has only sharpened. The fear that fueled Columbine has metastasized, fed by media cycles, social media algorithms, and a political climate that thrives on paranoia.

The odd image of the shooters going bowling the morning of their massacre still lingers. To me, it suggests this: we can’t spend our lives fearing what we can’t make sense of. The real danger lies not in the inexplicable, but in the culture of fear we’ve chosen to accept. That’s the question the film leaves us with, and one America still hasn’t answered: Should I be afraid?

Image Credit of Rotten Tomatoes

Sources:

Richard J. Bonnie and Rebekah Hutton (Eds.) Consensus Study Report. “The Impact of Active Shooter Drills on Student Health and Wellbeing.” National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Nationalacademies.Org, 2025, www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/the-impact-of-active-shooter-drills-on-student-health-and-wellbeing.

Gramlich, John. “What the Data Says about Crime in the U.S.” Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 24 Apr. 2024, www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/04/24/what-the-data-says-about-crime-in-the-us/.