The Fight to Decorate Yourself: Why Accessorizing is Inherently Political

By Natalie McCarty

To decorate oneself is not a frivolous indulgence; rather, it is a declaration. In a world obsessed with shrinking, streamlining, and sanitizing the human experience, adornment becomes one of the few accessible acts of personal sovereignty. Jewelry, beyond being ornamental, is a statement, intention, and sometimes, confrontation.

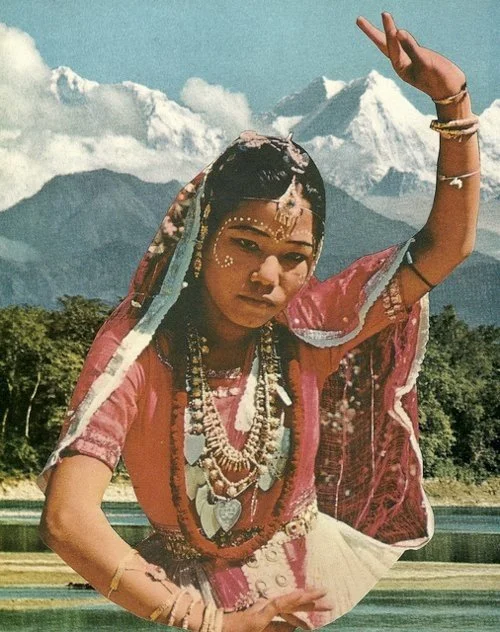

Image Sourced through Pinterest

Adornment has been central to human civilization since its earliest days. Archaeological digs have unearthed 100,000-year-old Nassarius shell beads in Morocco, which are some of the earliest evidence of symbolic human behavior. In ancient Egypt, jewelry signified divine protection and social rank. Pharaohs were buried with amulets and elaborate gold pieces to guide them into the afterlife. In the Mughal Empire, intricate gem-encrusted jewelry served both as wealth and as art, showcasing mastery in craftsmanship that also signaled imperial power.

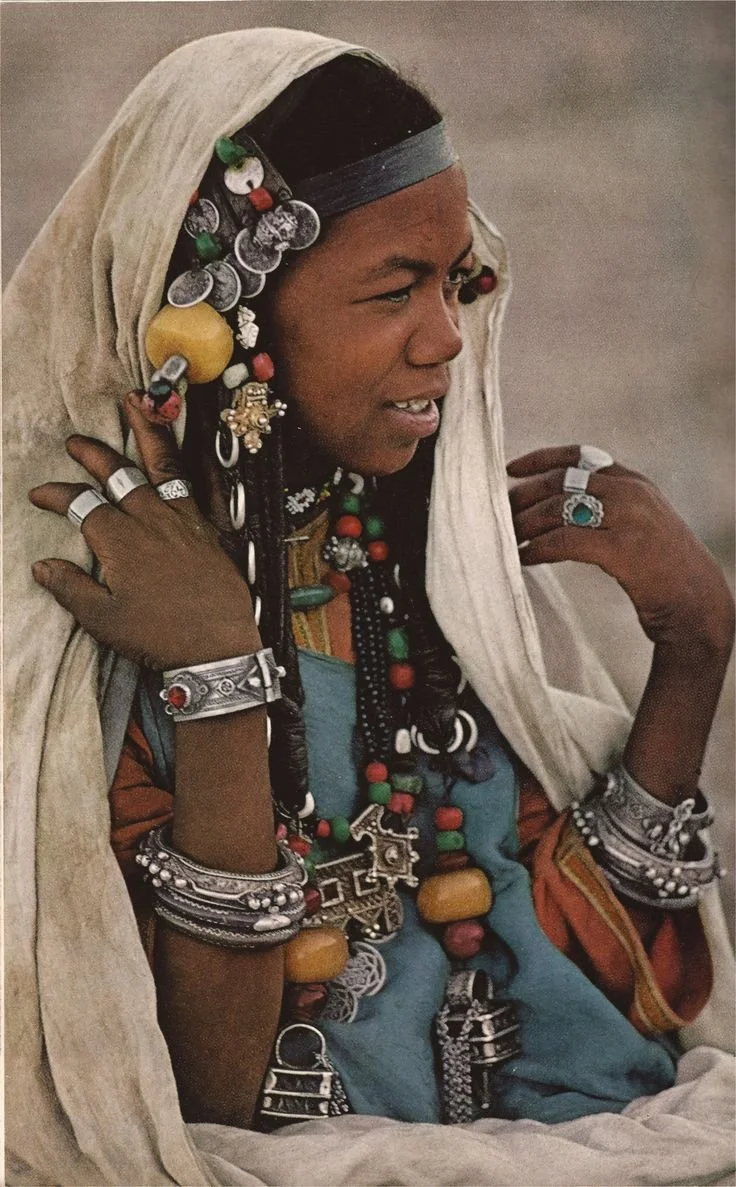

Image Sourced through Pinterest

In West African cultures, gold was not only a symbol of wealth but a spiritual material that connected individuals to their ancestors. The Ashanti people of Ghana developed elaborate gold weights and adornments that carried cultural, social, and economic meaning. In Indigenous North American societies, turquoise and silver work reflected tribal identity, trade, and spiritual protection.

Image Sourced through Pinterest

Adornment has always intersected with power, status, and identity, and it has always been political. Colonization brought violent extraction of these decorations of self: looted gold, plundered jewels, stolen cultural artifacts that now sit behind glass in European museums. Adornment became a battleground where cultural expression clashed with imperial domination.

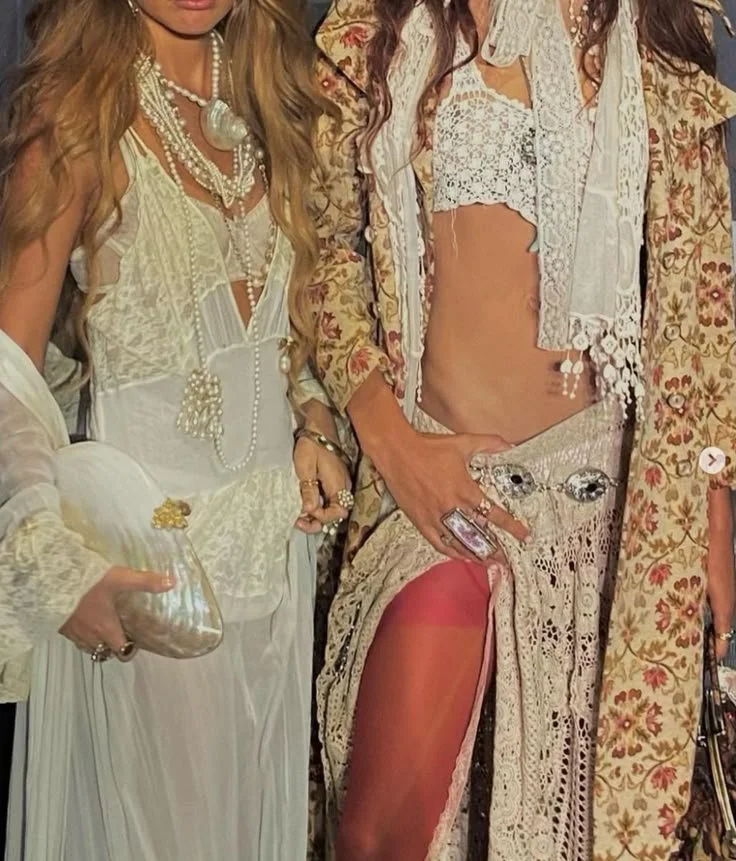

The modern obsession with minimalist aesthetics, with the curated neutrality of “quiet luxury,” the algorithm-fed monotony of beige influencers, functions as a new form of control. It rewards restraint and punishes excess. But maximalism pushes against that tide. To layer your fingers in rings, stack bracelets up your arms, let your necklaces tangle and shine, is intentional visibility in a world that prefers you muted.

Image Sourced through Pinterest

Accessorizing refuses erasure. It disrupts the expectation that bodies must conform to specific molds to be seen as professional, tasteful, or respectable. Even as fashion cycles attempt to commercialize the aesthetic of maximalism, the raw impulse to decorate oneself remains untouchable by commodification. It is ancient. It is instinctive.

There is profound meaning embedded in objects we choose to carry on our bodies: family heirlooms, gifted pieces, trinkets from travels, and cheap market finds that carry inexplicable emotional weight. Jewelry becomes a living archive and a tactile memory bank worn daily. The clinking and shining of each piece is evidence of a life being lived.

Capitalism has long attempted to flatten individuality into digestible trends. But true ornamentation resists that flattening. It demands space, both physically and symbolically. It speaks in contradiction to an increasingly homogenous landscape that worships subtlety as virtue.

Image Sourced through Pinterest

To decorate oneself, especially with intention and excess, is to reject the passive consumption of style and assert control over your own presentation.

In a world so heavily mediated and surveilled, adorning yourself is one of the last accessible declarations of personal authorship. It is a small revolution we carry on our bodies every single day.