The Folk Revival: Why Folk Music's Resurgence Reflects Our Political Moment

By Natalie McCarty

In the uncertain and disorienting landscape of modern politics, an unlikely genre has once again found itself at the cultural forefront: folk music. Its reemergence is not accidental. As global movements reckon with racial injustice, economic inequality, climate crises, and political instability, folk music has resurfaced as a raw, accessible, and powerful tool of collective expression. But to understand this resurgence, we must first trace folk's complex and deeply political roots, particularly its Black origins, and its cyclical role in American protest movements.

Long before folk became synonymous with images of white men holding acoustic guitars, it was a vessel of Black resistance. Spirituals sung by enslaved Africans, field hollers, work songs, church hymns, and the early blues all laid the foundation for what we now recognize as American folk. These songs were survival mechanisms, oral histories, and coded messages. They carried the weight of oppression but also the possibility of liberation.

Image Sourced through Pinterest

Folk music, in its truest form, was born from the resilience of Black communities, its rhythms and melodies deeply tied to their lived experiences.

Image Sourced through Pinterest

One of the most haunting examples of this intersection is Billie Holiday's "Strange Fruit." Originally a poem written by Abel Meeropol, the song became an unflinching indictment of America's history of racial terror. Holiday's chilling rendition transformed it into one of the earliest and most potent protest songs, setting a precedent for how folk and jazz could confront systemic violence.

Image Sourced through Pinterest

As the 20th century unfolded, white artists like Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger popularized folk music for a broader, often white, American audience. Guthrie's "This Land Is Your Land" and Seeger's union anthems gave voice to the working class, connecting folk's origins with broader economic struggles. Their music was radical, calling out capitalism, injustice, and war. Seeger, famously blacklisted during the McCarthy era, understood the inherent subversiveness of folk: its simplicity made it accessible, but its message made it dangerous.

Image Sourced through Pinterest

The 1960s saw folk's most visible political era, led by figures like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. Dylan, whose early works like "Blowin' in the Wind" and "The Times They Are A-Changin'" became anthems of the Civil Rights Movement, was heavily influenced by the Black blues tradition and the spirituals of his predecessors. Baez, a fierce advocate for civil rights and nonviolence (who continues to use her songs in protest to this day), used her platform to amplify the struggles of the marginalized, often performing alongside Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Image Sourced through Pinterest

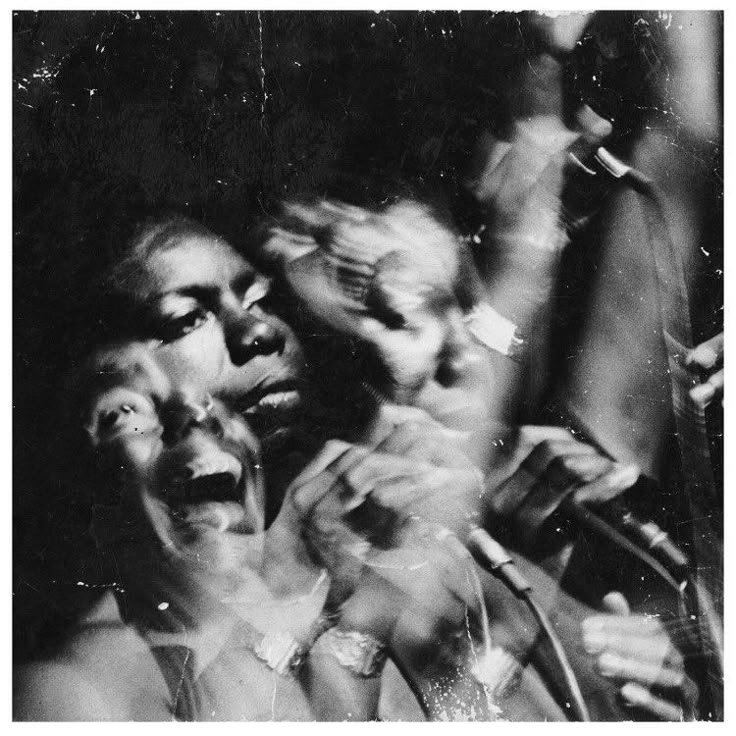

Yet, while the popular image of the ‘60s folk scene is often whitewashed, it's impossible to ignore how deeply Black music continued to inform its evolution. Nina Simone, often overlooked in conversations about folk, infused the genre with haunting clarity. Songs like "Mississippi Goddam" and "I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free" became searing indictments of American racism. Her work blurred the lines between folk, jazz, and soul, illustrating how these genres are deeply intertwined.

Image Sourced through Pinterest

Even popular culture has begun to reexamine this lineage. The success of the recent film A Complete Unknown, exploring Bob Dylan's early years, only resonates because the political climate today feels eerily reminiscent of the late 60s and 70s–a time of immense social upheaval, civil rights battles, and generational unrest. The film's popularity underscores a cultural yearning to revisit and understand the role of protest music in shaping consciousness during periods of instability.

Similarly, films like Ryan Coogler’s Sinners have found renewed relevance, capturing the moral tension, generational fractures, and collective questioning that define our current moment. These narratives, much like folk music itself, tap into an undercurrent of resistance, reckoning with the complexities of identity, faith, and justice.

Folk music's capacity for reinvention has always made it uniquely responsive to political moments. Today, its resurgence feels particularly urgent. Artists like Rhiannon Giddens, Joy Oladokun, Allison Russell, and others are reclaiming folk's Black roots while using the form to confront systemic injustice. The stripped-down nature of folk — a guitar, a voice, a story — cuts through the noise of digital culture. It reminds listeners of the power in simplicity, in collective grief and hope, in protest and perseverance.

In an age of disinformation, polarization, and cultural fragmentation, folk music is returning to what it has always been: a people’s music. It reflects not just a longing for authenticity, but a collective refusal to accept silence in the face of oppression. The folk revival is necessary. It's a reminder that even as history repeats its darkest chapters, the voice of the people will continue to sing, carrying forward the songs of resilience born generations ago.