The James Franco Revival: Aestheticizing Victimhood

By Reese Carmen Villella

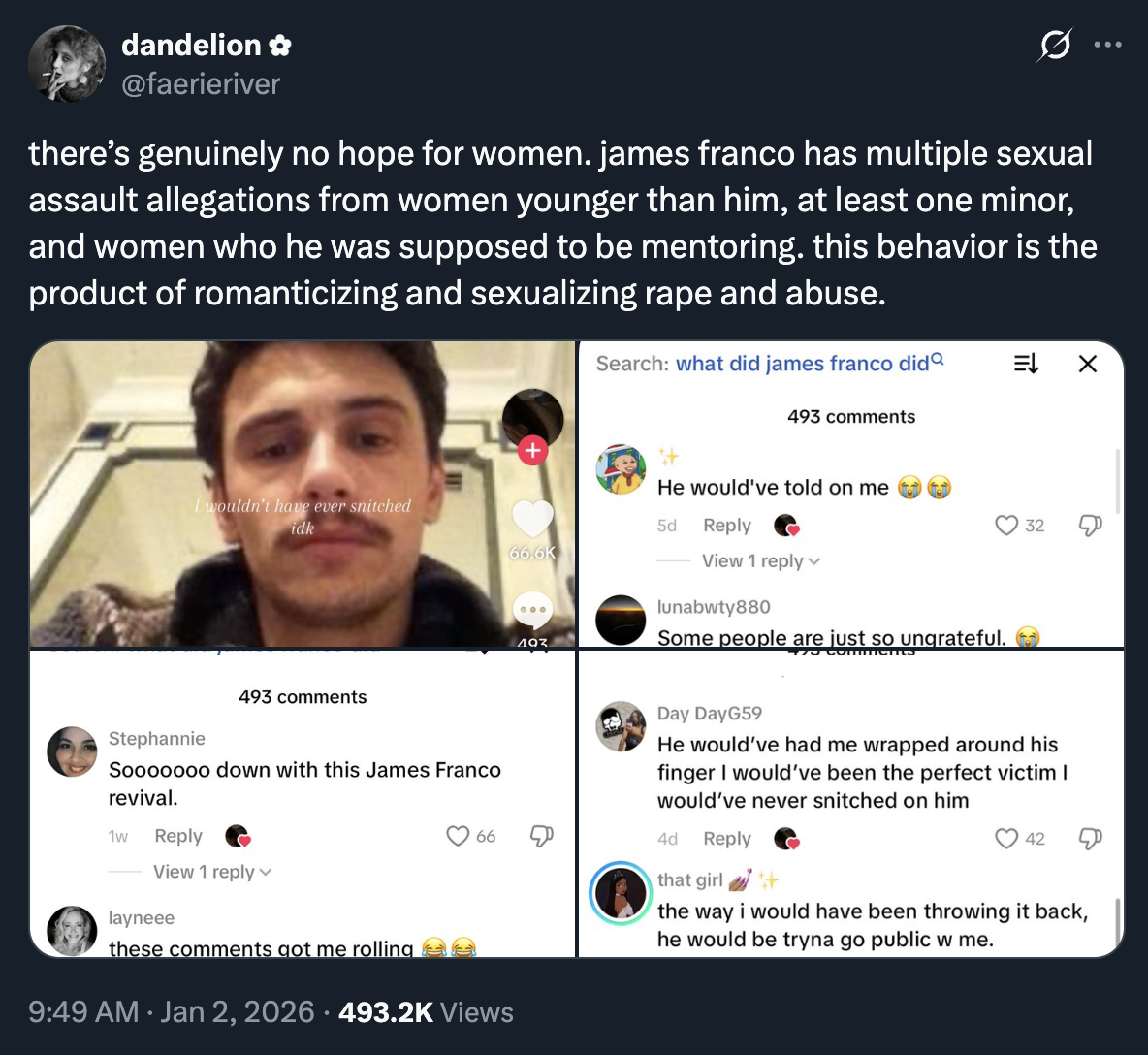

It’s a tale as old as time: I was scrolling on Twitter the other day when I stumbled across something repulsive and misogynistic. I came across this tweet, which included screenshots of the comment section on a TikTok about James Franco with the caption “I wouldn’t have ever snitched.”

If you don’t know what this is in reference to—several women, four of whom were students or mentees at Franco’s now-defunct acting school, Studio 4, filed a lawsuit alleging that Franco and his associates exploited the school to create a “pipeline” of young women subjected to sexual misconduct under the guise of professional mentorship. Accusations included pressuring students into performing sexual acts, staging unscripted topless scenes, and even removing protective guards during explicit filming. These allegations were not his first controversy; in 2014, he admitted to “bad judgment” after attempting to arrange a meeting with a 17-year-old girl via Instagram.

So, someone naturally decided to put together a compilation of attractive photos of James Franco with the caption “I wouldn’t have ever snitched.” The TikTok and its comment section reveal a disturbing mindset that being victimized by someone like James Franco could somehow be considered a privilege. It frames sexual abuse as desirable because of his fame, attractiveness, and wealth. Commenters echo this sentiment: one writes, “he would’ve had me wrapped around his finger I would’ve been the perfect victim I would’ve never snitched on him,” while another adds, “he clearly didn’t choose well cuz truly I would’ve been super glad.” And, perhaps the most unsettling: “Some people are just so ungrateful.”

What these comments illustrate, whether intentionally or not, is a misunderstanding of how abuse operates. They recognize Franco’s power, wealth, and charm as positives or attributes that make him “desirable.” In reality, these same traits were tools he allegedly used to exploit women. By framing victimization as a kind of honor or adventure, the TikTok and its commenters echo the rhetoric that has long been used to silence survivors: implying that reporting abuse is absurd, ungrateful, or unnecessary, and that women who resist are missing out.

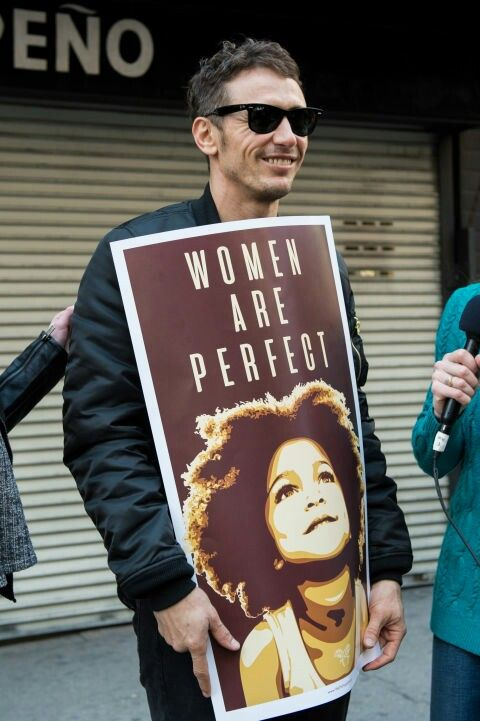

Emma McIntyre, Getty Images

The person who shared the screenshots on Twitter explains this dynamic clearly: “This has become a trend where women think they’re edgy or sexually liberated for wanting to ‘fix’ or even willingly fall victim to abusive men. CNC, porn, and rampant misogyny leads to rape and abuse becoming associated with kink and sex rather than patriarchal violence.” In other words, the commenters on this video are not just making tasteless jokes; they are participating in rape culture by reframing sexual exploitation as a choice or fantasy, rather than recognizing it as coercion and abuse of power. This framing normalizes predation and minimizes the harm done to survivors, perpetuating the very structures that protect abusers.

As if it couldn’t get any worse, I then discovered that this isn’t an isolated incident, that this “Franco Revival” is actually a trend on TikTok, with users posting flattering photos of Franco alongside captions about “snitching” on him. The comment sections are particularly revealing:

“I would of [sic] never snitched on daddy”

“It was something about how he tried to meet up with a 17 year old chick at a hotel and she blabbed to everyone about it”

“No one forced her to do it”

“It was the students choice”

“Fr they was so lame”

“Nah cuz that girl was lucky… lowkey”

“Don’t let the woke people see this”

These comments show a mixture of acknowledgment and minimization. Unlike fanbases of figures like Johnny Depp, whose supporters deny any wrongdoing entirely, Franco’s fans admit that something wrong happened--the repeated use of the word “snitch” implies that they understand a transgression took place. Yet they simultaneously downplay the severity, arguing that the victims were of legal age, that participation was “their choice,” or even framing it as a form of luck. This rhetoric mirrors the same patterns in rape culture: it recognizes abuse but rewrites it as consensual or desirable, effectively excusing predatory behavior while shaming survivors for speaking out.

Participants in this trend are normalizing sexual predation as something romantic or flattering, rather than abusive. Even as they acknowledge wrongdoing, they fail to grapple with power dynamics, coercion, and the systemic ways Franco allegedly exploited his position.

Many of the commenters seem fixated on the fact that Franco’s victims were legal adults. This reasoning is deeply flawed: being of age does not preclude abuse. The class-action complaint, Tither-Kaplan et al. v. Franco et al., makes this clear. Franco allegedly used his now-defunct Studio 4 acting school as a vehicle for exploitation, offering acting opportunities to students in exchange for participating in sexualized activities, nudity, or performing in explicit scenes. Students were even required to sign over rights to nude auditions and filmed sex scenes under the guise of professional mentorship. The lawsuit described these practices as a deliberate attempt to create “a pipeline of young women who were subjected to his personal and professional sexual exploitation in the name of education.” Specific allegations include Franco removing protective guards covering actresses’ genitalia during a simulated oral sex shoot, as well as pressuring students to perform sexual acts under his professional authority. The abuse extends beyond Studio 4: former girlfriend Violet Paley alleged that Franco forced her to give him oral sex in a car while they were dating, and he also admitted to attempting to meet a 17-year-old girl at a hotel when he was 35.

In June 2021, Franco settled two legal disputes for a total of over $2.2 million: $894,000 for the two women citing sexual exploitation, and a larger class-action settlement involving Studio 4 students who claimed they had been defrauded. These settlements underscore the seriousness of the allegations, even though Franco did not admit wrongdoing.

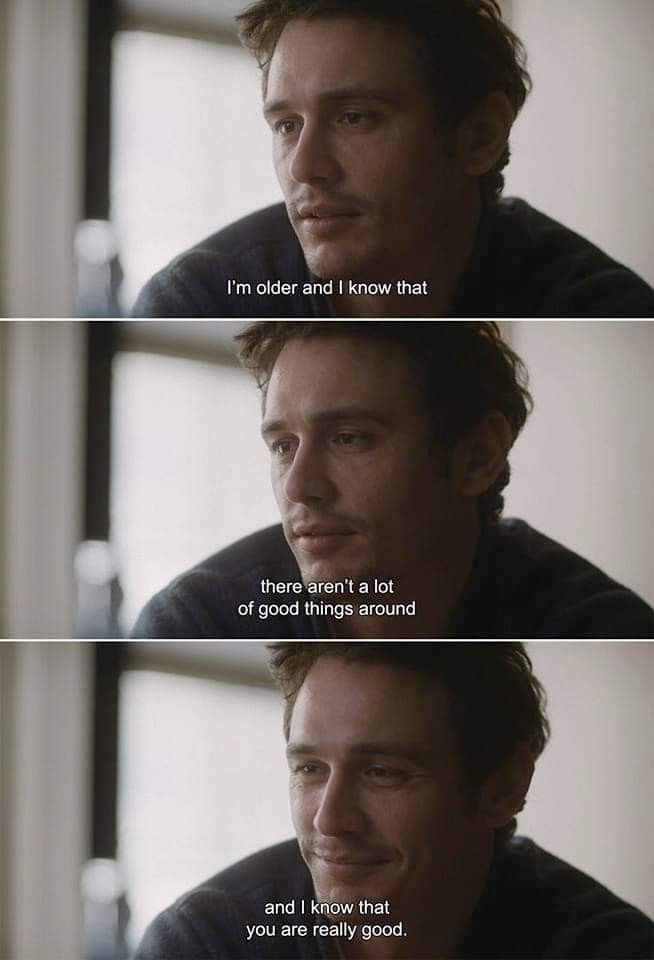

Courtesy of Maker Studios

Many TikTok commenters misinterpret these dynamics, suggesting the Studio 4 women were simply students Franco had consensual relationships with. In reality, the plaintiffs were victims of sexual exploitation under his professional authority. The plaintiffs never alleged that they were in relationships with Franco, but rather, that sexual boundaries and industry standards were violated in academic contexts. While Franco also admitted to sleeping with students, this is not the primary reason he was “canceled.” Whether commenters are referencing the legal problems Franco faced or the admission of sleeping with students, both of these actions represent an abuse of power, and neither can be excused or trivialized.

By framing abuse as consensual or glamorous—he was hot, she should feel lucky—the TikTok trend mirrors a larger societal problem: minimizing predation when the abuser is attractive, famous, or wealthy, and misunderstanding the coercive power dynamics at play.

I keep coming back to the use of the word “lucky,” as if being targeted by a famous, attractive actor somehow makes sexual exploitation desirable. But there is nothing lucky about being a victim of sexual violence, coercion, or exploitation. The very traits (wealth, fame, charm) that commenters admire are precisely what were used to manipulate and victimize these women. The idea of luck ignores the power dynamics, the pressure, and the psychological manipulation inherent in these situations.

It’s worth considering how longstanding narratives like this may have shaped victims’ understanding of or reconciliation with the abuse. I didn’t want this, but he’s James Franco. I should feel lucky, I should feel good about this. He’s a celebrity. Everyone has a crush on him. Why does it still feel wrong? Attempting to rationalize abuse does not change the circumstances. Sexual abuse is abuse, regardless of the perpetrator’s status, attractiveness, or relationship to the victim. Being rich, famous, or “hot” does not make predation excusable or desirable, and framing it as “lucky” only reinforces harmful myths that normalize coercion and silence survivors.

In an ironic, but not unfamiliar, twist, these harmful narratives are made more compelling because the videos themselves appear unassuming: cute, dreamy, and aesthetically appealing. They use songs by Melanie Martinez, Lana Del Rey, or renditions of “Hopelessly Devoted to You,” paired with pink fonts, filters, and coquettish visuals. This styling presents predation as innocent, whimsical, or even desirable. By turning victimhood into an “aesthetic,” the videos make it appear aspirational.

Framing abuse as a taboo fantasy rather than coercion makes the content feel playful or edgy rather than dangerous. This mirrors patterns often seen in grooming or sexual abuse: an abuser in a position of power shows affection or attention initially, creating a sense of privilege or specialness. As boundaries are crossed, the victim is manipulated into believing they should feel lucky or grateful for the attention, for the opportunity, or for the relationship itself. By aestheticizing this dynamic, these TikTok videos trivialize abuse and normalize the idea that exploitation can be desirable if the abuser is attractive, famous, or charming.

Why am I bringing this up now? These allegations were brought to light years ago, and the lawsuit was settled in 2021. For starters, this TikTok trend has emerged quite recently; most of the referenced videos are from December 2025. But James Franco is hardly the issue here—it’s the dialogue and culture we have around sexual exploitation. This is not an isolated or harmless trend; it is part of a larger, radical rise in misogyny that normalizes and eroticizes breaches of consent.

Franco as the predatory teacher in Palo Alto

Across corners of the internet, narratives like this are becoming increasingly mainstream. In just a few minutes, I came across multiple disturbing tweets claiming that women enjoy rape, including: “Polish women enjoy being raped. Therefore they don't report it afterwards,” “Some women enjoy being raped,” “I think the majority of feminists have rape fantasies,” and “there is a hilariously shocking amount of girls who are actually into rape.” And it’s not just anonymous accounts spreading these ideas. Far-right commentator Nick Fuentes--a real charmer--went even further, claiming: “A lot of women want to be raped. ... A lot of women really want a guy to beat the shit out of them, but part of it is that they have to pretend that they don't.”

This rhetoric is actively pushed online, with men attempting to convince women that sexual abuse is desirable, deserved, or even enjoyable. They frame “rape fantasies” and CNC (consensual non-consent) as a form of empowerment or a “trauma response,” suggesting that victims are reclaiming control through fantasy. How many times do these messages have to be repeated before women start to internalize a fantasy that isn’t real, authentic, or their own?

The problem is that aestheticized portrayals of abuse, like the Franco TikToks, blur the line between fantasy and reality. In a controlled, imagined setting, such ideas may be presented as edgy or playful. But when those fantasies are projected onto real-life situations, the perspective shifts. Sexual predation is no longer scandalous; it is excused, trivialized, or even celebrated. By framing these scenarios as “cute” or romantic, the content normalizes coercion and erodes the understanding of consent, particularly among younger audiences who consume it.

And so, to return to the original TikTok caption “I wouldn’t have ever snitched,” it’s worth reconsidering what that really implies. Are commenters claiming they wouldn’t speak up because James Franco is so dreamy? Or is it because, deep down, they know that if they were in that position, people like themselves would dismiss their trauma, blame them, and label them ungrateful?