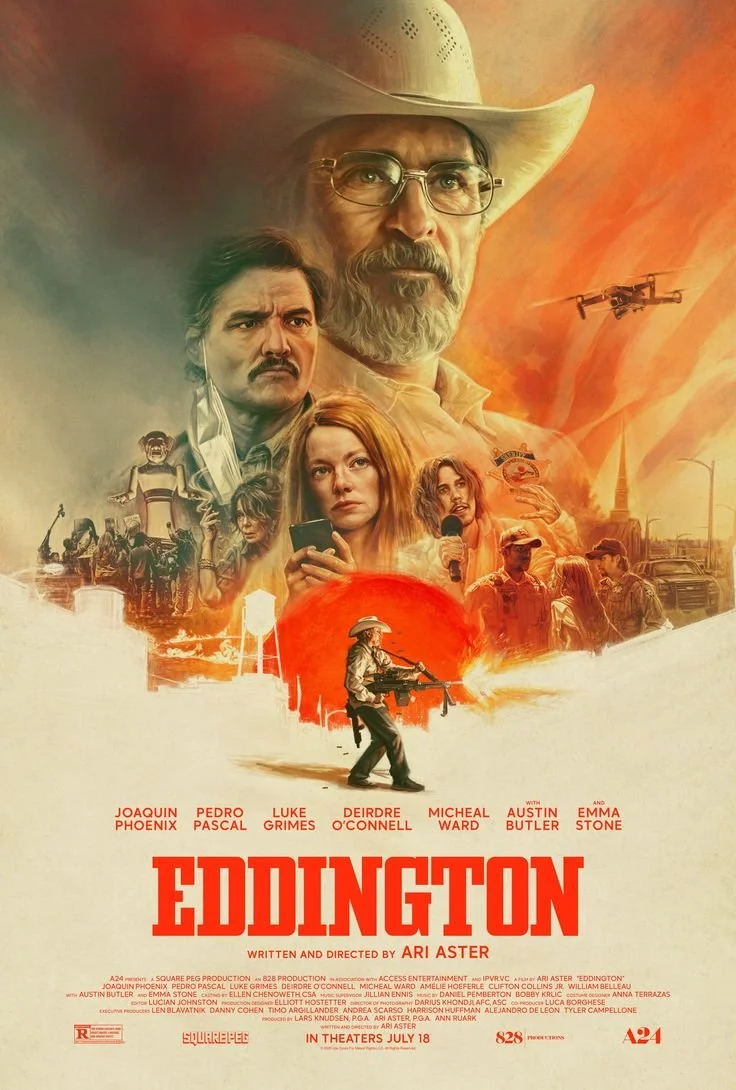

'Eddington': A Post-Pandemic Doom-Scroll of a Film

By Natalie McCarty

“You can’t keep your own office going, but you’re going to run mine?”

Image Courtesy of A24

Eddington, Ari Aster’s latest film, is so sure of its ambition yet so uncommitted to coherence that it becomes, paradoxically, a reflection of the very moment it’s trying to dissect. It opens with a sense of clarity, even urgency—a half hour of sharpness that captures the eerie absurdity of the pandemic years. But then, like a feed you can’t stop scrolling, it keeps going. And going. Not because it has more to say, but because it can’t resist the inertia of its own chaos.

To watch Eddington is to feel the logic of the algorithm seep into cinema. Scenes don’t build; they flicker, flare, and abandon themselves. Characters deliver monologues as if they’re recording podcasts for themselves, each sealed in their frequency, never really connecting, which I guess is (in part) the point. Regardless, the film itself scrolls through cults, political conspiracies, pandemic-era malaise, and American mythmaking with the same aimless rhythm of a late-night binge through Twitter (or X now, whatever the hell) threads. The tonal shifts critics have called disorienting—Western stoicism one moment, cult-horror dread the next, then a deadpan comedy beat—are indeed flaws. Though I understand the intention of structural mimicry, Eddington is just fragmented, incoherent storytelling.

The camera participates in this collapse. Darius Khondji shoots every glowing screen with the reverence usually reserved for faces. Phones, dashboards, and laptops are framed as if they’re the true subjects of the film, while the humans are reduced to silhouettes on their own periphery. That, admittedly, was a little cool as it’s a sly, almost cruel inversion: you find yourself empathizing with the screen more than the person holding it. The landscapes feel smaller than the data farms, and the result is a kind of visual claustrophobia. If the film is about anything, it’s about our surrender to the devices we carry in our pockets, the way it has quietly assumed more narrative authority over our lives than any one person ever could.

Image Courtesy of A24

And yet, amidst this suffocating digital haze, Joaquin Phoenix oddly grounds it as Joe Cross. I liked him in this kind of role. It wasn’t spectacular, but I think he was perfectly cast. And then there’s Pedro Pascal. His presence as the mayor, Ted Garcia, is just so perfect; I love him in anything and everything. However, on that note, why do all films and shows he’s in get so hellbent on killing off his character? Don’t they know that the story always dies with him? Pascal has this rare ability to make even the flimsiest material feel alive, so when the film predictably erases him, they destroy their chances of landing a good Rotten Tomatoes score.

Also, not that we need to spend too much time on this point since Ari Aster didn’t either, but the most interesting character in this (besides Michael) was Austin Butler’s little freak character of Vernon Jefferson. Now, that was a hideously underused performance. That was an actually interesting character with his ability to lure you in only to remind you that there is no real “there” there. I would have loved to see more of him.

Image Courtesy of A24

What I will give Eddington credit for, though, is its understanding that the pandemic infected perception as well as it did bodies. We came out of it divided with splintered truths, “fake news,” and trapped in parallel realities we refuse to reconcile. Long after the virus receded, the epistemic damage remained. Aster presents this point through the conspiracies that flare up in the film that aren’t presented as villainous or absurd; they’re just there, ambient, like the haze of misinformation that coats everything we now see from the conservative party.

There’s a temptation to call Eddington overstuffed, or unfocused, or even indulgent. And it is all of those things. But to reduce it to a failure of craft is to miss what it’s doing: it’s replicating an environment. Watching it feels less like digital immersion into the endless, numbing churn of a culture that stemmed five years ago and continues to no longer distinguish between the profound and the trivial.

Whether you find that profound or insufferable depends entirely on your tolerance for ambiguity. But if you walk out unsettled, even annoyed, maybe that’s the only appropriate reaction. Eddington is less a film than a mirror or a documentation of time. Truthfully, I think this is going to be better in the future when more time has passed and this, unfortunately, becomes a “period piece.”