Why Won’t Marvel Let Women Be Big?

By Laurel Sanders

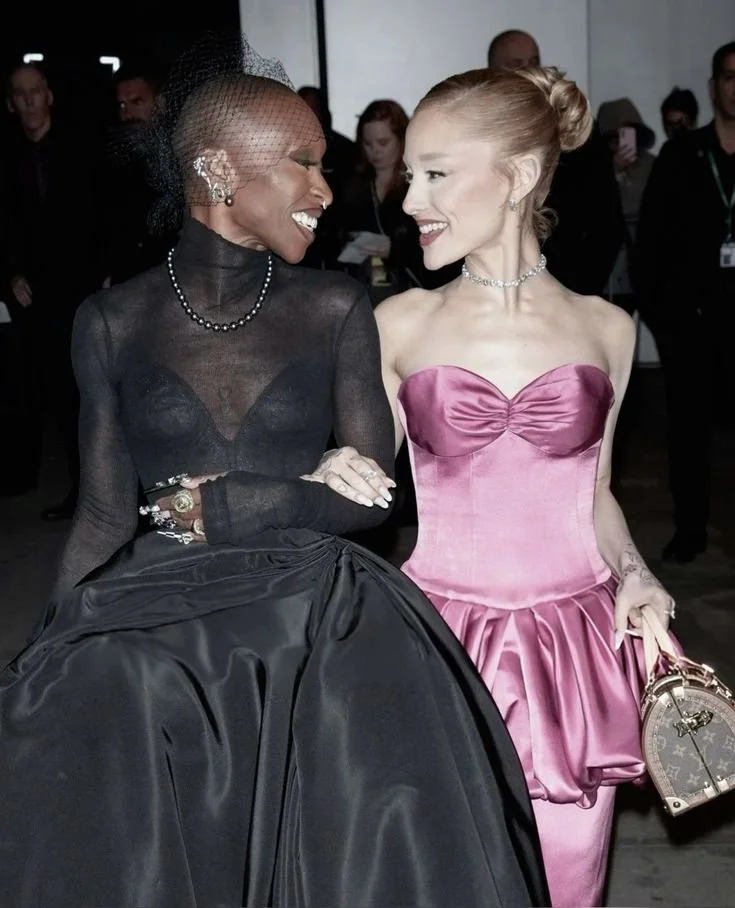

You may recall just a month or so ago, the international phenomenon and highly anticpated films, Wicked: For Good, was released. Even if you didn’t see it, it was nearly impossible to escape the sheer volume of marketing and press surrounding its release. And almost inevitably, whenever Wicked: For Good came up in conversation, it was followed by the same question: What is going on with Ariana Grande and Cynthia Erivo? From their close friendship to their bodies, these two women were publicly scrutinized and harshly criticized during what was, objectively, the peak of their careers. I can’t count how many conversations I had (often with people who hadn’t even seen the film) speculating about their bodies and hypothesizing eating disorders. If they didn’t have eating disorders before, one could argue they might now, after the entire planet seemed intent on dissecting how “freakish” they supposedly looked.

Image Sourced through Pinterest

There are many possible explanations: the reality of eating disorders in Hollywood, which are both common and incredibly difficult to overcome, or simply atrocious lighting and ill-fitted costumes. But regardless, this became a major cultural moment—one that revolved heavily around women’s bodies and what is now being dubbed the “skinniness epidemic.” From Natalie Dyer’s appearance in the latest season of Stranger Things to Meghan Trainor’s recent weight loss, it seems as though all women are once again being inspected, evaluated, and discussed. Much of this anxiety appears rooted in fears surrounding Ozempic, Hollywood’s latest weight-loss obsession. And to be fair, that fear is understandable, especially as the drug is increasingly romanticized, normalized, and distributed at scale. Still, criticizing thin women instead of fat women does not make the conversation any less harmful. We are simply repackaging the same obsession with women’s bodies.

So what does this have to do with Marvel? Maybe not much at first glance—but it feels essential to address our evolving (and still deeply flawed) language around women’s bodies before asking a question I’ve been thinking about for a long time: Why won’t Marvel let women be big?

When I ask this, I’m not solely referring to fat versus thin bodies, though it is worth noting that I can’t think of a single plus-sized woman in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, which now spans 37 films and countless Disney+ series. Meanwhile, there are several notable male characters with larger bodies: Ned Leeds, Gilgamesh, Red Guardian, and even Thor, who was famously placed in a fat suit for Avengers: Endgame. It’s difficult to imagine Marvel giving a female character a similar storyline. If Black Widow had spiraled into depression, drank heavily, and gained weight, I doubt it would have been played for laughs in the same way.

To be fair, I haven’t kept up with every recent MCU project. It’s nearly impossible at this point, as Marvel has clearly shifted from quality to quantity. Perhaps I’m missing some hidden example of meaningful body diversity for women… but I strongly suspect I’m not.

Image Sourced through Pinterest

Beyond body size, Marvel also refuses to let women be physically big in a superhero context. The most obvious example is the Hulk: a massive, destructive green monster whose entire identity is rooted in size. Naturally, Marvel introduced She-Hulk (because what’s more reliable than a female version of an already successful male character?), and while she is tall and muscular, she ultimately just looks like a tall, green woman. Compare Mark Ruffalo to the Hulk, and the transformation is shocking: a small, nerdy man becomes an uncontrollable force of destruction. But when a woman transforms, she remains conventionally attractive: a sexy lawyer rather than a terrifying monster.

I’ll admit this is a surface-level critique; I didn’t watch She-Hulk. The show’s justification seems to be that women are better at managing anger, which allows them to maintain control. That explanation makes sense to a degree, but it doesn’t negate the visual comparison Marvel deliberately invites by naming her She-Hulk. She is not allowed to truly be the Hulk—only a softened, palatable version of him.

The same pattern appears with the Wasp, the counterpart to Ant-Man. Ant-Man’s suit allows him to shrink and grow to enormous size, often in climactic moments meant to awe the audience. The Wasp, however, is never granted that same spectacle. She remains small, and worse, poorly written. In the comics, the Wasp was one of my favorite characters growing up: a founding Avenger who was funny, flirty, fashionable, feminine, and strong. In the MCU, she’s reduced to a generic “She-EO” archetype, a watered-down version of the same female badass we’ve already seen with Black Widow and Gamora. If it worked once, Marvel simply copy-pastes it again.

Image Sourced through Pinterest

But the most painful example is Ms. Marvel, aka Kamala Khan. Kamala is a Pakistani-American teenager from Jersey City and Marvel’s first Muslim superhero. Her powers allow her to shapeshift, stretch, and, most importantly, embiggen, as she famously calls it. Her relationship with her body is central to her origin story. When she first gains her powers, she dreams of Captain Marvel and expresses a desire to be her, except wearing the “politically incorrect” costume and kicking butt in giant wedge heels. Kamala wakes up transformed into a giant, white, blonde, hyper-sexualized version of Captain Marvel.

This moment is rich with symbolism. Kamala’s new body grants her power; she saves her bully from drowning, but it also invites objectification. Strangers praise her appearance, while a homeless man sexualizes her and tells her to cover up. Her powers serve as a clear metaphor for puberty: sudden, confusing, empowering, and frightening. By the end of the chapter, Kamala reflects, “For the first time, I feel big enough for this. Big enough to have greatness in me. Big enough to do anything.” The message is unmistakable. Being physically big is synonymous with taking up space, embracing identity, and becoming a hero.

None of this translates to the MCU. While the Ms. Marvel show is charming, her powers are completely rewritten. Instead of her body changing, she generates purple, glowing energy constructs. Occasionally, these resemble large hands or stretched limbs, but it’s not the same. Her physical body remains unchanged and visually unthreatening. The likely justification is that stretching powers are hard to make look good in CGI. But when Fantastic Four arrives, Mr. Fantastic is allowed to keep his stretchy, strange body. Marvel didn’t rewrite his entire power set, and fans would have rioted if they did.

Kamala is meant to take up space. She is supposed to be awkward, weird, and larger than life. Her physical power is inseparable from her emotional journey. Removing that is not a neutral adaptation choice; it fundamentally alters her story.

So why did Marvel make these changes? Why won’t Marvel let women be big? I don’t have a definitive answer beyond the obvious: sexism and risk aversion. Marvel seems unwilling to take chances with women unless those risks have already been tested on men. And by the time women are allowed to follow, the idea has lost its impact.

Most women in the MCU don’t even have superpowers; they’re simply exceptionally skilled fighters, or their abilities are largely mental, like Scarlet Witch or Mantis. This is the result of years of sidelining women’s stories. Take the infamous “girlboss” scene in Avengers: Endgame, where every female character suddenly assembles on the battlefield in what the Russo brothers clearly believed was a feminist triumph. Most of these women have never spoken to each other. Only one has her own standalone film. And notably absent is Black Widow, the franchise’s first major female character, who was killed off so the men could be emotionally motivated by her death.

This moment isn’t empowerment; it’s box-checking. And Marvel repeats it because they believe representation can be condensed into a single shot rather than built through meaningful storytelling.

Marvel is in a precarious place right now, facing superhero fatigue and diminishing returns. But as a cultural touchstone spanning over two decades, how it represents women matters. How it depicts bodies matters. While I’m skeptical of panic-driven narratives like the “skinniness epidemic,” there is undeniably a lack of body diversity in Hollywood, especially in fictional worlds where anything should be possible.

Let She-Hulk be angry and terrifying. Let Kamala Khan be strange and larger than life. Let the Wasp have a personality, and then let her be big, too. Marvel may be struggling to hold onto its audience, but for female fans, that disappointment has been building for much longer.